Classic D&D adventure module review

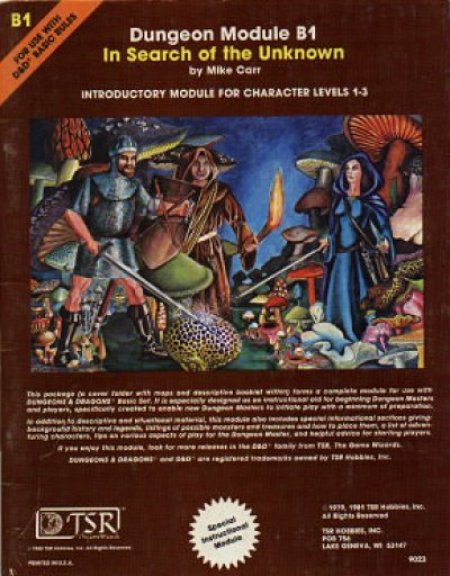

In Search of the Unknown, by Mike Carr – Basic D&D, 1979, 1981

In Search of the Unknown, by Mike Carr – Basic D&D, 1979, 1981

Introductory module for character levels 1-3

32 pages plus the separate cover with maps on the inside faces. This adventure has 56 numbered areas.

Generally, this adventure is a basic dungeon crawl; there is no plot beyond general exploration and fighting and looting. The unique feature of this module is that all the room and area descriptions leave the choice of monsters and treasure placement completely up to the Dungeon Master (DM).

The first five and a half pages of the book cover lots of notes and guidance for new DMs: Notes for the Dungeon Master, Preparation for the Use of the Module, Time [how to keep track of], Computing Experience, How to be an Effective Dungeon Master. The next two pages cover the adventure location background, random legends (true and false) the PCs may know about the dungeon, and the general description of the dungeon environs.

The adventure background explains that the dungeon, named the Caverns of Quasqueton, was built by two adventurers named Rogahn and Zelligar, “a fighter of renown” and “a magic-user of mystery and power.” The two used the location as a base of operations for a while, but then they disappeared on their last foray. Their dungeon base has been essentially vacant for a time.

If only one had the knowledge and wherewithal to find their hideaway, there would be great things to explore! And who knows what riches of wealth and magic might be there for the taking???

The actual dungeon area descriptions start on page 8, after the wandering monster chart. To give you a feel for the dungeon inhabitants, here are the wandering monsters:

1-4 orcs

1-2 giant centipedes

1-6 kobolds

1-2 troglodytes

2-5 giant rats

1-2 berserkers

All the monsters are listed in the “old school” stat block style: AC 6, HD 1, hp 6, 4, 3, 1, #AT 1, D 1-6 or by weapon, MV 90’ (30’), Save F1, ML 8.

There is no boxed text for the DM to read aloud to the Players—the boxed text concept was still a few years from being conceived when this module was written and published. There is no real organization to the room description and information text, so to run the adventure smoothly, the DM would need to either memorize all the text or go through making notes and highlighting information he thinks he’ll need. Most of the rooms have lots of text in many paragraphs, so this lack of organization in the room keys is a weakness of the design. But it is also a standard style in most adventure modules of the time.

Each area description ends with “Monster:” and “Treasure & Location:” lines. This is where the DM is supposed to write in his own choice for monster and treasure. The list of monsters and treasures to place is near the end of the book.

In the monster list, there are 25 choices but a few are repeated with only the number appearing and hit points differing. There’s probably 15 to 20 different monsters listed. There are 34 treasures listed—no repeats—including coins, gems, jewelry, and magic items. The author says this, in bold, for the monster list:

Important: although there are 25 listings, the Dungeon Master should only use 16-20 of them in the dungeon, placing some on each of the two levels in the rooms and chambers desired. The remainder are unused.

And he says this, also in bold, for the treasure list:

Special note: Even though 34 treasures are listed here, only between 15 to 25 of them should actually be placed in the dungeon by the Dungeon Master. The remainder should go unused. When treasures are chosen and placed, a good assortment of items should be represented: some very valuable, some worthless, most in between.

The dungeon itself is large: two levels, each covering over 400 by 300 feet. There are 56 numbered areas, and almost every one has something interesting about it to give PCs something to look at, mess with, figure out, or just be confused by. There are numerous tricks and traps, secret doors, pools of liquids, statues, a maze of doors, a spiral corridor, and at least one of all the other standard dungeon gimmicks.

Pages 26 to 30 contain lists and information on pre-generated characters to be used as PC adventurers or NPC henchmen and hirelings. The only things really pre-generated are the character ability scores. Everything else, including personalities, equipment (including some magic items), spells, and levels is given in lists for random determination. It would probably be as easy to just create a character normally as to use the information in this section to determine and finish one of the pre-generated characters.

The last two pages is one full page of information for players including setting info, “Here is the standard background setting for all players to read prior to their first adventure,” and play tips. These play tips are great, and can be very useful even for today’s players: Be organized, cooperate, be on your guard, know your limits, etc. All good stuff.

Overall, this adventure is a good idea for new DMs and Players. The guidance at the beginning for DMs and the end for Players is solid and wise. Letting the DM place monsters and treasure is a good way to introduce a DM to creating his own dungeons. But the lack of organization for the extensive text makes this adventure very difficult to run without very thoroughly reading and rereading and making notes before the game. All adventures require, or at least need, the DM to read and understand it beforehand, but every room in this adventure is pretty detailed, with lots of information.

The gimmicks (tricks, traps, neat stuff, etc.) in this adventure is great for new Players to experience. Just determining what is in the glass and earthen jars of the wizard’s workroom can fill an hour of first timer fun. Experimenting with the various pools in the room of pools can entertain new Players for another hour. New Players and DMs can get a whole lot of fun and good times exploring this dungeon, but anyone experienced with the base gimmicks of a D&D dungeon may find this old hat. And anyone looking for a plot or story will find little in this adventure to entertain them. Some areas and gimmicks of the dungeon just don’t make sense; anyone expecting or preferring a dungeon layout to make sense for its purpose (current or previous) will find this dungeon frustrating.

Bullgrit

Categories:

Categories:

In Search of the Unknown, by Mike Carr – Basic D&D, 1979, 1981

In Search of the Unknown, by Mike Carr – Basic D&D, 1979, 1981