Classic D&D adventure module review

Classic D&D adventure module review

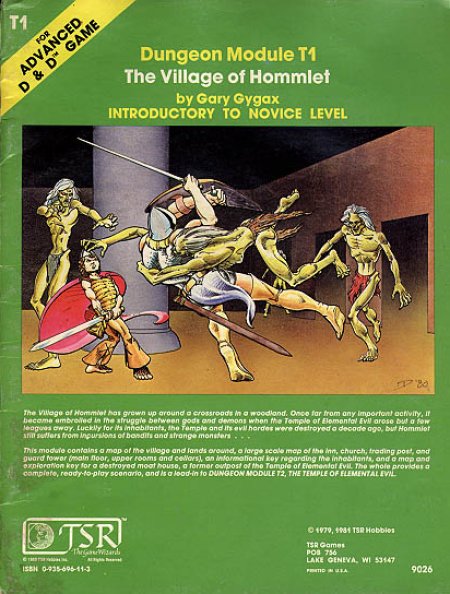

The Village of Hommlet, by Gary Gygax – Advanced D&D, 1979, 1981

Introductory to novice level.

24 pages plus the separate cover with maps on the inside faces. (3 blank pages backing maps.) The adventure has 35 numbered areas.

The first thing you notice about this book is the dense text. Each page is two columns, with small margins, and long paragraphs. There’s a lot of text in this book.

The first page is the background for Hommlet and the starting set up for the party entering the area. Hommlet has quite the storied history, being the closest normal town to the Temple of Elemental Evil. The next half page is notes to the Dungeon Master (DM) on running this adventure.

The first page is the background for Hommlet and the starting set up for the party entering the area. Hommlet has quite the storied history, being the closest normal town to the Temple of Elemental Evil. The next half page is notes to the Dungeon Master (DM) on running this adventure.

The area here, as well as that of the Temple (contained in a separate module), was developed in order to smoothly integrate players with and without experience in the Greyhawk Campaign into a scenario related to the “old timers” only by relative proximity.

[The actual Temple of Elemental Evil module wouldn’t be published for another 6 years, in 1985, as the first “super module.” That module would include this adventure, republished.]

The biggest chunk of text in this book is the building by building key to the village: eight and a half pages covering 33 numbered areas of mostly mundane buildings and village folk.

6. HOUSE WITH LEATHER HIDE TACKED TO THE FRONT DOOR: This is the home and business of the village leatherworker (0 level militiaman, leather armor, shield, sling, hand axe; 4 hit points). With him live his wife, her brother (a simpleton who does not bear arms), and 3 children of whom the eldest is a 12 year old boy (0 level militiaman, leather jack, buckler, sling, dagger; 2 hit points). The leather-worker is a jack-of-all-trades, being shoe and bootmaker, cobbler, saddler, harnessmaker, and even fashioning leather garments and armor, the latter requiring some time and a number of fittings and boiling. He is not interested in any sort of adventuring. Sewn into an old horse collar are 27 g.p. and 40 e.p. as well as a silver necklace worth 400 g.p.

17. MODEST COTTAGE: A potter is busily engaged in the manufacture of various sorts of dishes and vessels, although most of his work goes to passing merchants or the trader. He has a variety of earthenware bottles and flasks available for sale. The potter (0 level militiaman, padded armor, shield, glaive; 3 hit points), his wife, and four children (two boys are 0 level militiamen, padded armor, crossbow, spear; 4 and 2 hit points respectively) all work in the business. A crock in the well holds 27 g.p., 40 s.p., and 6 10 g.p. gems. They are of the faithful of St. Cuthbert.

[Bolding above as it appears in the book.]

I cannot see a true need for the amount of detail such mundane villagers receive. A few of the villagers are agents of one side or the other in the Good and Evil contest, and the text explains them in as much detail as the normal folk. Only a handful of the NPCs, those with levels in a class, are given names in the text.

There is a lot of coin and magic treasure in this town. The detail and highlighting of these items, as well as the combat stats of every able-bodied male in the village, suggests perhaps the author expected the Player Characters (PCs) to explore the homes and businesses as they would a dungeon. I can’t believe that was actually the intention, but the information on the village buildings looks exactly what you normally find in a dungeon write up (including the dungeon at the end of this book).

A few of the buildings are detailed down to the rooms inside, even with full maps: The Inn of the Welcome Wench tavern (3 floors), the Traders’ Establishment, the Church of St. Cuthbert (3 floors), and the Guard Tower (7 floors). There’s no set adventure to be had in these locales, so scaled maps seem unnecessary. I guess they could be useful for first-time DMs to see what a tavern or church in a D&D world would look like, but I would think illustrations would be better than combat grid maps.

The map on the inside of the book cover shows the entire village at 110 feet to the inch scale. The individual building maps cover pages 17 – 22 (one sided pages).

For the village of Hommlet, there’s a great deal of individual building and person detail. The adventure site, The Ruins of the Moathouse, located 3 miles from the village, covers pages 12 – 16, with the two-level map on pages 23 and 24.

The ruined moathouse “was once the outpost of the Temple of Elemental Evil,” and its ground level is now occupied only by some vermin and a small group of human brigands. The wandering monster encounters are:

2-8 giant rats (see #13., below)

Scraping noise (materials shifting)

Giant tick overhead (see #16. below)

Squeaking and rustling (rats in the floor below)

2-5 brigands (reinforcements for #7., below)

Footsteps (trick of echoes – party’s own)

The dungeon level of the moathouse is the true place of Evil in hiding. An ogre, some zombies, gnolls, bugbears, ghouls, and a sizable group of evil soldiers for the Temple of Elemental Evil are all lead by Lareth the Beautiful, “the dark hope of chaotic evil”.

The PCs could become heroes for rooting out and destroying this small bastion of dangerous villains. They could also come out quite wealthy.

The text of this adventure is dense, with most of the areas written in single paragraphs. There’s no boxed text to read aloud to the Players, so the DM has to read the information carefully before the game session, and probably make notes and highlight information to run the encounters. As evidenced here and in other adventure modules, this author tends to write encounter information in a stream of consciousness style—description, monsters, and treasure are in a single long paragraph for each encounter area, with no set organization.

All the monsters are listed in a modified “old school” stat block style: (H.P.: 21): AC 5; HD 5 +1; Move 9″; 1 attack using bardiche for 2-8 +5 (7-13) hit points of damage.

The adventure is simple and straight-forward enough for novice players wanting to explore a dungeon and fight evil monsters and men, but the opposition in the dungeon is pretty numerous and strong for a party of 1st-level PCs. Even if the adventurers are themselves numerous (the text does not state how many PCs the adventure design expects), they’ll have to be tactically savvy with a mind to retreat when necessary, if they hope to survive this dungeon delve.

Overall, this book spends many pages and much detail on the mundane villagers of Hommlet compared to the adventure. But, the book is titled The Village of Hommlet, so it is actually giving the DM what it advertises. This book is a village, home base source book with a small adventure appended to the end rather than an adventure module.

Bullgrit

Categories:

Categories:

Classic D&D adventure module review

Classic D&D adventure module review Classic D&D adventure module review

Classic D&D adventure module review The first page is the background for Hommlet and the starting set up for the party entering the area. Hommlet has quite the storied history, being the closest normal town to the Temple of Elemental Evil. The next half page is notes to the Dungeon Master (DM) on running this adventure.

The first page is the background for Hommlet and the starting set up for the party entering the area. Hommlet has quite the storied history, being the closest normal town to the Temple of Elemental Evil. The next half page is notes to the Dungeon Master (DM) on running this adventure. Classic D&D adventure module review

Classic D&D adventure module review